This week I tweeted a few thoughts on my approach to teaching our undergraduate “Research Methods in Sociology” and the positive response encouraged me to do a slightly more detailed write-up here.

Before I launch into that, a bit of background. I teach at small university that feels more like a SLAC. We are primarily undergraduate-serving, and many of our students are first generation college students or international students. My position is in the Sociology & Criminal Justice Department (that might include Education now, too, after pandemic-related restructuring). This was historically a Sociology department with an optical crime and justice concentration, but in recent years increasing student interest drove us to create a fully-fledged CJ major. We now offer the Sociology and CJ majors, related minors, and I believe an Education Studies minor. Oh, and we are located in downtown Boston — like right downtown, a stone’s throw from the Common — and like to emphasize local connections and opportunities to leverage our excellent location.

A core course in the curriculum for both Sociology and Criminal Justice majors is SOC-214 Research Methods in Sociology. This is, as the title suggests, a 200-level course, though I find I get a lot of juniors and seniors who have delayed taking the course because they find research methods intimidating. I typically have a mix of Sociology, Criminal Justice, and Environmental Studies majors (ES is a separate program but their students often take our courses as electives or as substitutions).

I have been teaching Research Methods for some years, both at my current institution and previously, and so my approach has evolved over time. I initially started out teaching Methods as I had been taught, fairly straightforward, from a classic textbook. I should mention that as an undergraduate, I actually failed my first Methods class and retook it. I earned an A the second time around, which indicates to me that the way we teach Methods matters a lot. My own views on the importance of Methods have taken a long journey, too, from thinking that Methods is a boring but necessary class to coming to see Methods as a great opportunity for creativity – I credit my graduate school Methods instructor for that new perspective. I see Methods as giving students a set of useful tools to use to creatively solve research problems, and that is what I try to communicate to them. That is, while many avoid the course because they think it will be heavy on mathematics (no), logic (kinda), and science (of course), I strive to show them that it can also be about creativity, problem-solving, social justice, and doing good in the world.

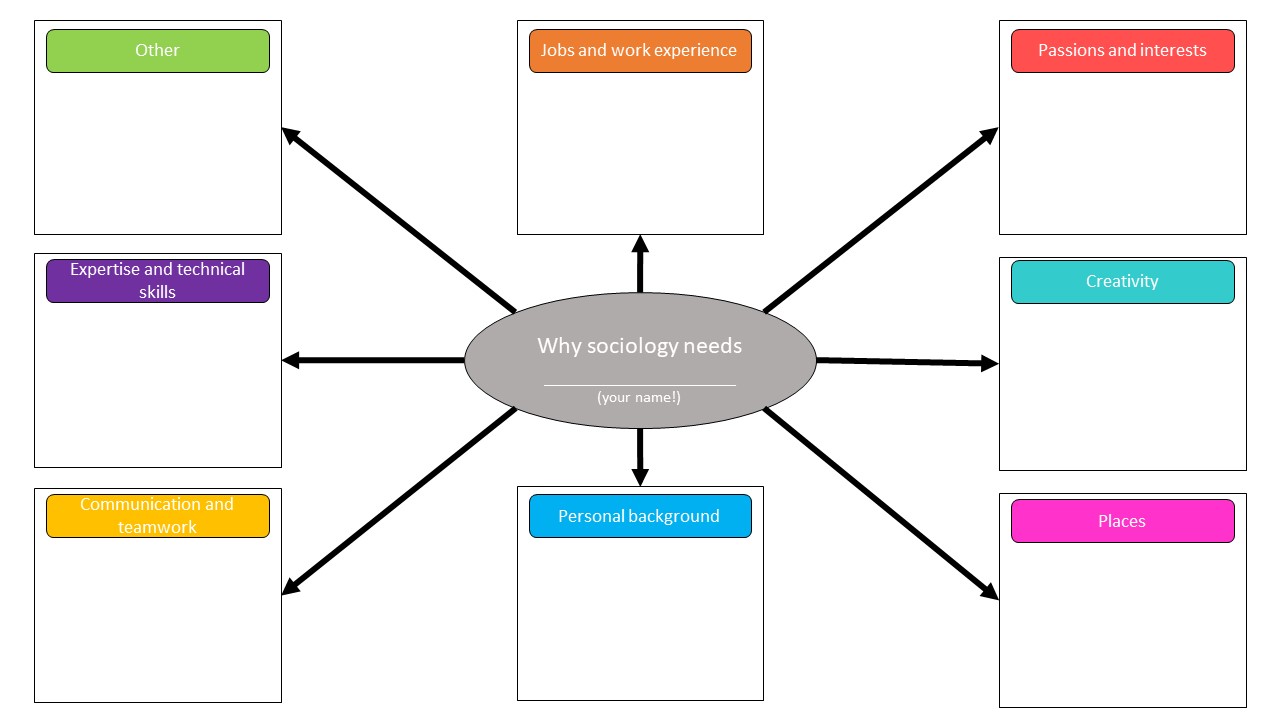

One of the first things I do in this course is asset mapping. The credit for my approach here goes to Kristin Wobbe and Elisabeth Stoddard’s Project-Based Learning in the First Year, which was first introduced to me when Rick Vaz spoke at an event hosted by my institution’s Center for Teaching and Scholarly Excellence. I know that students come into my course with some dread and trepidation, and many of my students come from marginalized populations and may feel they don’t necessarily belong in the classroom or in science. I want to address that up front. So at the start of the semester, as we talk about what science is, what social science is, what sociologists do, etc., I make sure to do an asset mapping activity in class (you can find my template here). I show them how my background positions me to ask and answer interesting sociological questions, from my time growing up in Australia and immigrating to the US, to my years working in retail and customer service, to the usual “go to” credentials like skills and education. I want them to think beyond their formal education and realize that many of the things they probably think are deficits are actually assets, and how important it is that we have their voices in science (if that is what they choose to pursue). After I show them how to fill out the map and give my own examples, I break them into groups to fill out their maps and discuss with their peers.

The traditional project for undergraduate Methods courses is (to my knowledge) the research proposal, and I have kept this for my course. However, I have changed my approach from assigning the proposal in whole to breaking it into multiple worksheets throughout the semester, helping students to think through the task of something like a “literature review” or “dissemination plan” by posing questions about their goals. This is still a work in progress, as I have found the lit review activity is not working quite as well as I had hoped, but it is an improvement over my previous formats.

Early on, I left the proposal project fairly open-ended and encouraged students to choose a topic that mattered to them, as I thought this would help motivate them (as it does me). This was well-intended but often disastrous. Students naturally gravitated toward highly-charged topics about which they held strong opinions: gun control or gun rights, abortion, social media, and others. These are important topics, of course, but for students new to the idea of scientific inquiry, these topics were often so important to them that they really struggled to create good research questions and designs that would measure reality, and not just their desired outcomes (e.g. “I’m going to design a study to prove that gun control doesn’t work”). I think they they also struggled with the abstract nature of just plucking a research question from the air and designing a study.

To address some of these issues, I decided to create more structure for my students. I decided to develop a survey for them to take at the beginning of class to measure their interests (as well as other useful info, like pronouns and preferred names/nicknames, concerns about the course, etc – click here for my survey questions). Then, based on the survey results, I developed five mock “requests for proposals” (RFPs) for students to choose from to shape their proposal projects (click here for some examples). Each RFP is written with some creative opportunity — after all, as researchers, we know that we may see 100 responses to a single NIJ RFP and all will be different! But the RFP helps to guide the students in their choice of topic (again, based on their interests), suitable designs, and importantly, the goals of the research. I think that this helps to ground the idea of research as a path to social change. Rather than pulling a question out of the air, they can see that they can use their skills as researchers to provide important information to people who need that it to make decisions and, hopefully, help others (this is highly motivating for my students, in my experience).

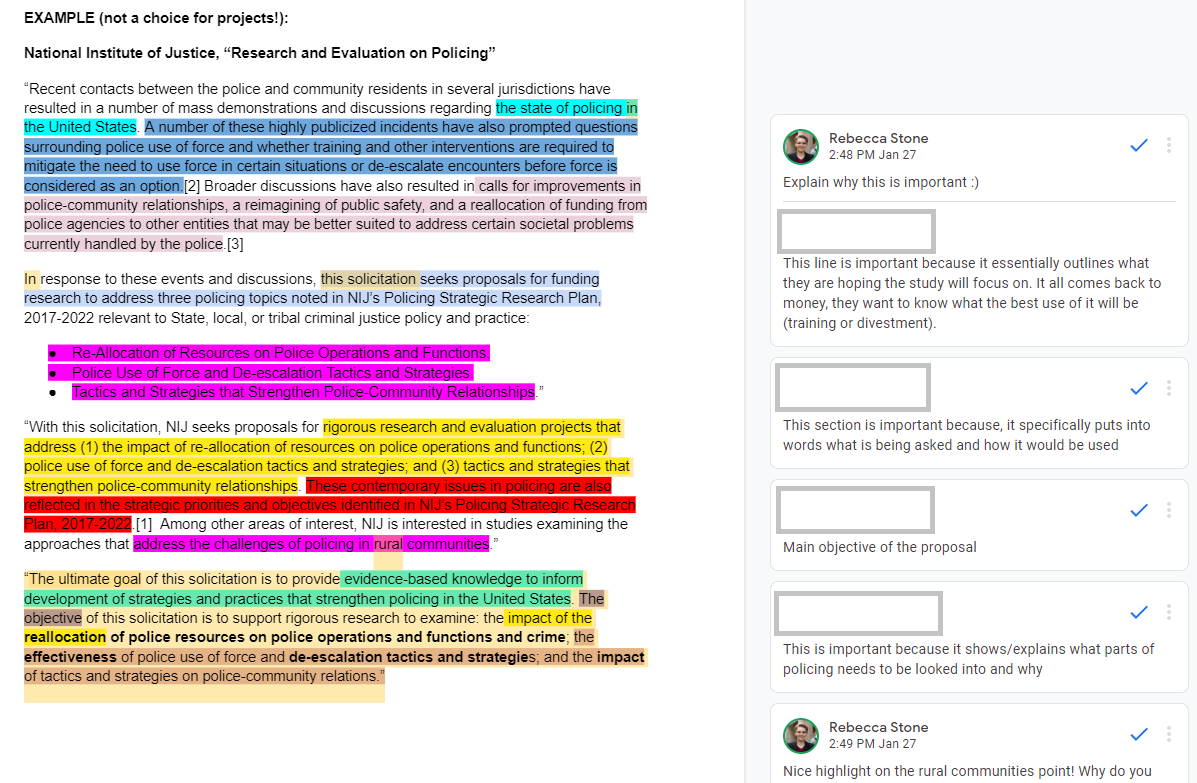

Another advantage of this approach is that I can take the opportunity to teach students about the reality of what research costs and how it gets funded, as well as the skill of reading an RFP and pulling out the critical information. I find, across my courses, that many students can read just fine but struggle to absorb the information that matters. They will read an entire textbook chapter word for word but could not repeat back to me what it said or what the key points were. I knew that I needed to support the development of this really important skill, and reading RFPs is a great way to do that. There are a lot of words, but ultimately the funder is looking for something fairly specific. Reading closely and highlighting specific requests and phrases helps to shape your proposal and make sure it aligns with the RFP, increasing your chances of funding.

We practice this skill in a class activity. This week, we did it Google Docs, as my institution was online for the first two weeks of the semester. First, students collaboratively read and commented on an example RFP (an old NIJ policing solicitation), identifying what they thought was important, and we had a discussion about that. I then presented the class with the five RFP options for this semester and created Zoom breakout rooms for each one, allowing students to self-select into the room for the RFP that most interested them. This worked well – because I had based the RFPs on their interests and tried to make sure everyone was covered, I ended up with an equal distribution of students across the rooms. Then, from their breakout rooms, they worked together to highlight and comment on their RFP text and brainstorm possible research questions. The example and mock RFPs were all in the same Google Doc, allowing me to stay in the same Zoom room and respond to their comments and highlights in real time.

Finally, narrowing student choices down to these five mock RFPs helps to build community, because it creates groups of students that are working on similar topics. It avoids some of the difficulties of group work (like quibbling over grades) while still allowing opportunities throughout the semester for students to work in their RFP group and pool their efforts for finding literature, thinking about measurement, and other proposal-writing tasks. This helps students meet others with shared interests and get some non-instructor support from their peers.

Proposal-writing is a worthwhile skill for students to learn, but we can do more to show the real-world importance of things like close reading of solicitations and using research to meet social needs. I am pleased with how my approach is working out but of course see plenty of room for improvement! I would love to eventually make this a truly project-based class where they can really do research in our community and create products for local organizations. I would also love to eventually move to a more “ungraded” format. For now, however, there’s a pandemic on and there’s a lot on my plate, so I think that my current model strikes a good compromise between my ideal and what is possible for me at the moment. I hope that the shared resources are useful for you, and if you do end up trying something similar in your courses, I would love to hear about it!