This piece appeared in the May 2022 edition of ACJS Today.

Download my assignment guidelines here.

I probably shouldn’t admit this so openly, but: as a criminal justice student, I really didn’t ‘get’ theory. My theory course seemed like a semester-long exercise in memorizing an endless litany of rival explanations for the same observations, all having experienced some amount of time in the disciplinary dustbin before being resurrected again by some new test finding “mixed support.” Why did we have so many theories? Why should I care about this?

My perspective on the importance of theory has, thankfully, evolved from my undergraduate years, and I think that the turning point was connecting with research on topics that seemed important and exciting to me, to real-world puzzles that I wanted to solve, and seeing how theory could help me to make sense of them. Now, as a professor who teaches Research Methods at the undergraduate and graduate levels, I am motivated to push students along the same journey I took, though hopefully a little more quickly, and help them to understand why theory matters in social science.

Rather than walk my undergraduate students through the Greatest Hits list of sociological and criminological theories, I decided to try and engage them with the idea of theory more generally. I returned to my own understanding of theory as a tool for puzzle-solving. Given a set of observations or pieces of data, how can we make sense of the relationships between them to better understand the “big picture”? I was inspired by a worksheet I found online that I traced back to Sociology Through Active Learning: Student Exercises (McKinney & Heyl, 2009). This helped me to develop guiding instructions for my students.

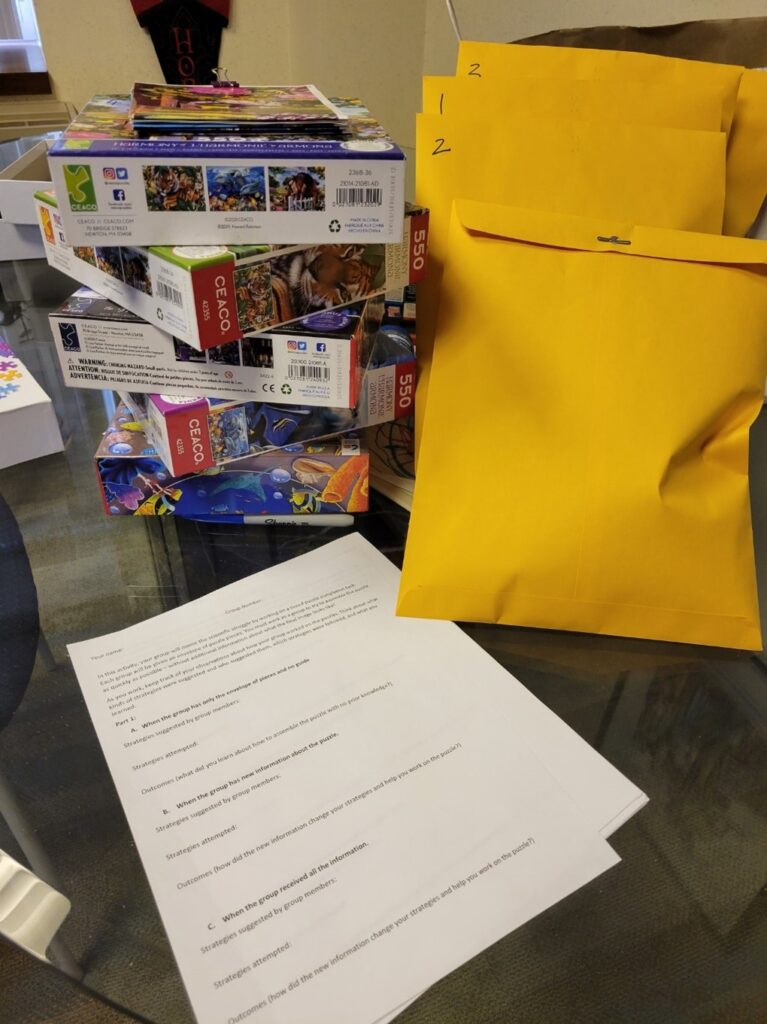

I prepared for the activity by purchasing some colorful puzzles. Here was my first challenge: I wasn’t sure how many pieces each puzzle should have in order to be sufficiently challenging for the students to reassemble in the class period. I ended up choosing 550-piece puzzles, but I would say that these were probably too challenging and larger pieces might have been easier. I then emptied each puzzle into a plain manila envelope and marked each envelope with a number. I left the puzzle boxes in my office but pocketed the picture guides for what the completed puzzles should look like.

In class, I lectured briefly about the scientific method, where theory fits into that cycle, and inductive vs. deductive reasoning. I then randomly sorted the class into groups of about five students each and gave each one a manila envelope with their puzzle pieces. Each student also received a worksheet with instructions. The back side of the sheet asked them to reflect on what the activity had helped them to understand about the role of theory in social science. I had my own goals for the lessons I wanted them to learn, but I was also prepared for them to make new connections that had not occurred to me.

Stage 1:

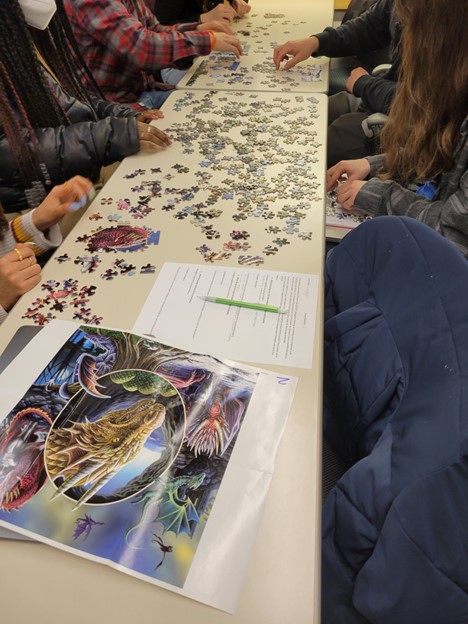

Their first task? Work together to assemble their puzzle – with no picture to guide them. They were advised to take notes on their strategies and thoughts about the activity as they worked. At first, groups started by turning all their pieces right-side up, dividing their pieces among group members, sorting pieces by color and finding corner and edge pieces. “At this point the process was intuitive and we were relying on puzzle instincts we already have,” wrote one student. In their reflection on the back of the worksheet, another student wrote “With no prior knowledge it is difficult to decipher how pieces of the puzzle work together” and that it “requires thinking intuitively, thoughtfully and cooperatively.” “We had an idea that it was an aquatic scene because of all the blue and colorful pieces, but didn’t know how it all fit together,” wrote another, and “Just because you have matching pieces doesn’t mean they will be easy to connect.”

Stage 2:

After allowing the students to struggle for 10-15 minutes with no guide, I handed out the folded-up picture guides and allowed them to see one quarter of the picture for their puzzle, providing them partial direction. The groups switched up their approach. For example, once one group realized that their scene had animals in it, they switched their focus to collecting pieces that seemed to belong to animal forms. “We continued to sort the pieces but this time it was based on a combination of color and images. For example, if we thought a puzzle piece looked like it belonged to a unicorn, we would pass it along” to the team member with other unicorn pieces. Collaboration also increased within groups at this stage, as team members stopped each collecting their own color of piece and started sharing with each other to help complete sections of the puzzle. One student wrote that “specific group members put together different parts that could be found; when one person couldn’t figure out a section, another tried.” Reflecting on this stage of the activity, students wrote that “It did validate our thoughts about the design of the puzzle,” “We were now able to recognize the goal (broadly) and work a little more strategically,” and “Instead of being all over the place, we were focused on one part of the puzzle.”

Stage 3:

Finally, after another 10-15 minutes, I instructed them to unfold the whole picture guide and see the completed puzzle image. Once the students had the full puzzle picture to work from, their strategies changed again. One student wrote that they “focused on completing sections and looking for pieces as we went, rather than sorting first.” Having the full picture “prepared us each to focus on our own specific sections,” and teams moved to “announcing who needs which pieces, or piece that we have that could help” another group member. Several students commented that work moved much more quickly at this stage, as “we had a better idea of what to look for and what we were doing. We were also able to see how the different parts of the puzzle were supposed to be connected to one another.” Their reflections emphasized that “communication was very important” and that “having more information helped us shift our strategies from small scale to large scale.” They worked more collaboratively because “we were able to connect some sections that we had originally worked on separately.”

Reflections

Students enjoyed the activity. The classroom was full of lively discussion and laughter, and many lodged lighthearted complaints that they were not able to complete their puzzles in our allotted class time. They took their worksheets home for the weekend to write their reflections and submitted them the following week. I read them with great eagerness to see what they had taken away from the activity, and I wasn’t disappointed! Here are some of their comments:

“Implementing theory was the primary way in which our group was able to start putting pieces of the puzzle together. After all of the pieces were turned over, the group quickly formulated a theory of what the final image could be… For example, the group determined that pieces with a static-looking grain were actually sand. Most of these sand pieces were edges, so we concluded that sand would make up the border of the puzzle. As we were allowed to see the partial image of the puzzle we confirmed our theory of the underwater scene but also came to rethink the role of some of the pieces… Ultimately, this exercise revealed that the beginning of a puzzle is much like the process of developing or working with a theory. The theory for our group became the foundation for our actions and observations, much like the practice of sociology or science in general.”

“Theory helps guide our research, much like the picture of the puzzle helped us better strategize to complete the puzzle. Similar to inductive reasoning, it is okay to start with little to no information, but as you work, you can observe what patterns you see and begin to put the pieces together (pun intended) and explain what it is that you observed.” [After seeing the full picture guide] “I feel like it turned from inductive reasoning to deductive reasoning, where I would assemble a series of similar pieces and we would discuss what looked like it would fit around the section that we knew.”

“Theory provides a frame of reference for organizing data. The outline of the puzzle is similar [in that it] acts as a frame of reference for the rest of the puzzle. […] There was a lot of trial and error involved, lots of experimenting. Each piece we attempted to match didn’t always fit, but we kept trying. Sometimes researchers come up with many different hypotheses to test because they disproved an earlier one. When data gathered disproves your hypothesis or theory, you must accept it. When puzzle pieces don’t go together, you need to accept. It. If you force them together, the picture turns out incorrect.”

This activity works very well in a Research Methods course and could also be used early on in a dedicated criminological theory course before launching into discussing specific theories. The puzzle approach turned theory from something abstract and academic to something students could literally hold in their hands. Having students work in groups also emphasized the collaborative nature of science and that many researchers may work on separate areas of a “puzzle” before realizing their areas fit together. And, as one student wryly remarked, the fact that the puzzles were too complex to be completed in the class period taught students that not all scientists live to see the results of their life’s work! Our contributions to science may not always be obvious but passing on a love of learning and discovery to our students reminds us that, as my favorite student reflection put it, “No matter how much we want to be independent, we still need each other. We depend on each other to complete our missing pieces.”

References:

McKinney, K., & Heyl, B. S. (Eds.) (2009). Sociology through active learning: Student exercises. SAGE Publications, Inc.